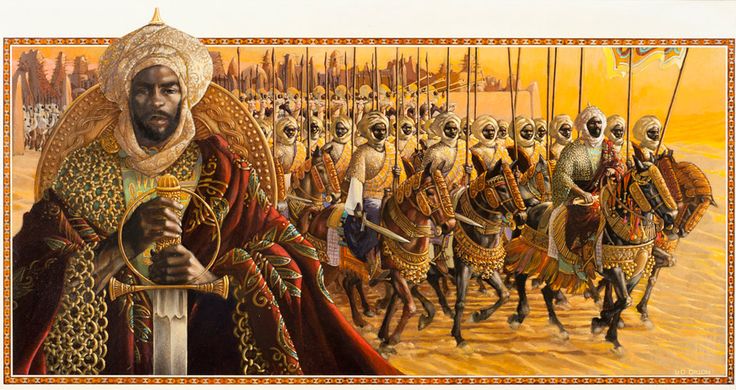

An artist’s impression of Mansa Musa with his hordes of soldiers. HISTORYNMOOR/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/CC BY-SA 4.0

In the fourteenth century Mansa Mūsā, emperor of the medieval Mali Empire of Africa, made a trip whose ripples were felt decades later. For the uninitiated, Ghana, Mali and Songhai were three of the greatest empires of the western part of Africa, south of the Sahara. Mūsā’s Mali empire spread 2,000 miles (3,219 kilometers) from the Atlantic Ocean to modern-day Niger. Some reports indicated it would take a year, at the time and with their means of transportation, to travel that breadth. The 14th-century traveller Ibn Battūtah noted that it took about four months to travel from the northern borders of the Mali empire to Niani, the Malian capital in the south. Mali formed a rich 24-city network of cities

Mūsā the Man

Mansa, which means ‘sultan’ or ‘emperor’ in the Mandinka language of West Africa, was immensely wealthy, prodigiously generous and profoundly pious. The empire’s source of riches was the natural resources of two highly productive gold fields renowned for some of the purest and most prized gold in the world. Nations scrambled for pure gold, especially for the minting of national coins in which they took much pride.

Mansa Mūsā took a legendary trip to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, to perform the annual Islamic Hajj pilgrimage with an entourage of 60,000 people, including a personal retinue of 12,000 slaves, all clad in brocade and Persian silk. On this trip were countless court officials, soldiers, griots (singing poets) and 500 slaves ahead of him each carrying a gold-adorned staff as he himself rode on horseback. Included in this Malian caravan were 80 baggage camels, each carrying 300 pounds of gold.

Either the grandson or the grandnephew of Sundiata, the founder of his dynasty, Mansa Mūsā came to the throne in 1307 (some reports record 1312) and took the said Mecca trip in the 17th year of his reign. His route from his kingdom’s capital of Niani (northeastern Guinea today) on the upper Niger River would take him first to Walata (Oualâta, Mauritania) and on to Tuat (now in Algeria) before making his way to Cairo.

Typically the journey to Mecca and back took a full year with long layovers in the Egyptian capital, Cairo. So en route, emperor Mansa Mūsā made a stop in Cairo to visit the Sultan. That stop… Well, the historian al-‘Umarī, who visited Cairo twelve years after the emperor’s visit, found the inhabitants of this Egyptian city, with a population estimated at one million, still singing the praises of Mansa Mūsā.

The Stop Market

To quote al-‘Umari, “The man flooded Cairo with his benefactions. He left no court emir… no holder of a royal office without the gift of a load of gold. The Cairenes made incalculable profits out of him and his suite in buying and selling and giving and taking. They exchanged gold until they depressed its value in Egypt and caused its price to fall.” That stop, stopped the market.

Apparently, so lavish was the emperor in his spending (one writer put it as “handing out gold like it was candy”) that he flooded the Cairo market with gold, thereby causing such a decline in its value that a dozen years later the market had still not fully recovered. It is believed that this visit caused many Muslim kingdoms in North Africa and others of European countries to desire to come to Africa. The rest, as they say, is history.

An African Leadership

The year of this much-talked-about trip was 1324. What does your history tell you was happening in the region of the world you hail from at the time? Since many Africans have been compelled to learn European history for obvious (colonial) reasons, we know that the 1300s were pretty dark days in Europe, fuelled by religious craziness, unfettered superstition and taken to the nadir by the arrival of the bubonic plague. Also known as Black Death, this pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people in Europe alone. Meanwhile the Black sultan Mūsā and his sub-Saharan African peoples were flourishing in ‘unimaginable wealth.’

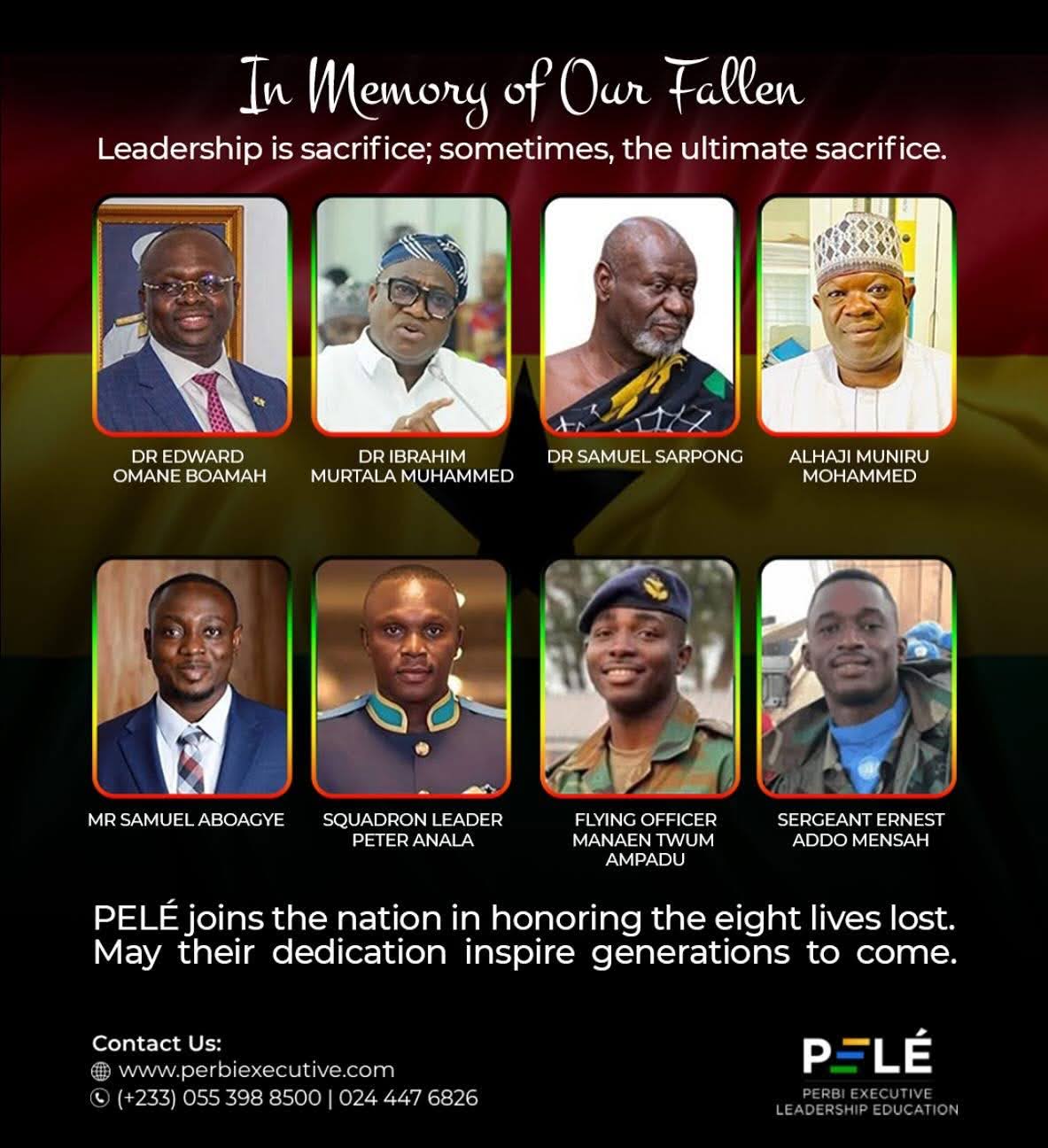

This detail is from Sheet 6 of the Catalan Atlas showing Mansa Musa crowned in gold. BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DE FRANCE/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

This detail is from Sheet 6 of the Catalan Atlas showing Mansa Musa crowned in gold. BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DE FRANCE/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

An elaborate 14th-century map called the Catalan Atlas features a prominent illustration of Mansa Musa seated on a plush throne, crowned in gold, holding a sceptre in one hand and a large golden orb in the other (see photo above). So says the map’s description: “This Moorish ruler is named Musse Melly [Mansa Musa], lord of the negroes of Guinea. This king is the richest and most distinguished ruler of this whole region on account of the great quantity of gold that is found in his lands.”

A Gold Bar for your Thoughts

This is no tall tale. Even today, evidence of Mansa Musa’s resplendent reign still stand, like the Djinguereber Mosque, in Timbuktu, Mali, which he commissioned to be built en route back from Mecca in 1327, paying the Granada (Spanish) architect Abū Ishā al-Sāhilī who had travelled back with him from Arabia 440 pounds (200 kilograms) of gold.

Mansa Mūsā’s army general had captured Timbuktu as a side show during the long Mecca pilgrimage. Emperor Mūsā would choose to spend significant time there on his way back to his own capital, eventually growing Timbuktu into “a very important commercial city having caravan connections with Egypt and with all other important trade centres in North Africa. Side by side with the encouragement of trade and commerce, learning and the arts received royal patronage” (Encyclopaedia Britannica). Eventually, three madrassas, including the still-standing Djinguereber, composed the University of Timbuktu, inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1988. The famed Malian city of Timbuktu was home to one of the largest libraries in the medieval world.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Under Mansa Mūsā (1307–32?), Mali rose to the apogee of its power.” From the look of things, Mansa Mūsā the Black emperor may have been the richest man to ever live. Sorry, Solomon. In fact, Celebrity Net Worth puts his net worth at $400 billion in today’s dollars, making Emperor Mūsā nearly twice as rich as Jeff Bezos. Amazing.

When it comes to Mansa Mūsā the Malian Maestro, however, too many get stuck on the money, but de Graft-Johnson concurs there’s more to legacy than gold: “The organization and smooth administration of a purely African empire, the founding of the University of Sankore, the expansion of trade in Timbuktu, the architectural innovations in Gao, Timbuktu, and Niani and, indeed, throughout the whole of Mali and in the subsequent Songhai empire are all testimony to Mansa Mūsā’s superior administrative gifts. In addition, the moral and religious principles he had taught his subjects endured after his death.”

Wait a minute. Stop. Where is all of Africa’s gold today; and where are her leaders of the Mansa Mūsā stock—immensely wealthy, prodigiously generous, profoundly pious, grand legacy-leaving?

References

De Graft-Johnson, John Coleman. ‘Mūsā I of Mali.’ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Musa-I-of-Mali

Galadima, Bulus and Sam George. 2024. Africans in Diaspora, Diasporas in Africa. Langham Global Library: Cambria, UK.

Roos, Dave. 2024. ‘African King Mansa Musa Was Even Richer Than Jeff Bezos, Some Say.’ https://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-figures/mansa-musa.htm