In medical school this wasn’t one of the diagnoses I was taught I could make but on the other side of the doctor’s desk, this may be an even more dire diagnosis than a clogged gut.

MAINLY MEN; BUT NOT ONLY

Last Sunday, in a suburban church in Montreal, this was the summary of the middle-aged chap who shared his life-long struggle of dealing with his past: “I don’t do emotions.” Me too! Well, no more.

In many world cultures, that is the manly thing to do; it is macho. Some women try it too 🙂 In fact, in my own language, there is a saying that, “Obarima nnsu;” to wit, real men don’t cry. Even as a little boy growing up in Scripture Union circles in Accra, I always knew there was something wrong with that statement because I considered no one more manly that Jesus Christ yet he wept. Ever since then, I haven’t had a problem with weeping (you probably have seen me weep!) but errm… not done so well with a whole range of other emotions.

FACE, FIGHT OR FLIGHT?

I still remember my rather unemotional response to one of my staff’s emotional appeal when he said, “I feel…” My immediate response was, “Good thing that it’s only a feeling; but what do you think?!…” I don’t need to tell you that conversation didn’t go very well after that.

The Lord has been particularly convicting me of my emotional immaturity since the beginning of this year. Prior to that, I was the kind of leader Ruth Haley Barton would describe in Parker Palmer’s words as having risen to leadership based on “extroversion, which means they have a tendency to ignore what is going on inside themselves. These leaders rise to power by operating very competently and effectively in the external world, sometimes at the cost of internal awareness… but the link between leadership and spirituality calls us to reexamine that denial of the inner life.” (Barton 2012, 44, emphasis mine).

In fact, I might never have picked up a book like Peter Scazzero’s The Emotionally Healthy Leader because hitherto the word ‘emotional(ly)’ anywhere put me off. But for Dallas Willard and Scazzero, I had never thought of my emotional life as specifically needing to be discipled! I certainly did not have the theological, mental or practical framework for that!

Scazzero astounded me and totally destroyed my perception of what spiritual formation consists of when he emphatically stated, “it is not possible to be spiritually mature while remaining emotionally immature!” (Scazzero 2015, 17). Gordon Smith drove the dagger deeper into my heart when he confirmed that “what is happening to us emotionally is not secondary to our spiritual experience, but may actually be—pun intended—the heart of the matter” (Smith 2014, 27).

And whole squadrons of the ancients agree, that “few things are so crucial to our growth in faith, hope and love as our capacity to be alert to the emotional contours of our lives” (28). Smith then adds another dimension, that not only are my emotions an area to be discipled for sure but they are also indicative, a dashboard sign, in the sense that “the depth of our hearts reflects the depth of our emotional lives; nothing so captures the inner recesses of our beings as what is happening to us emotionally” (28). In fact, St. Ingatius exhorts that we check for feelings of consolation and desolation in the Examen.

For all those as emotionally constipated as I used to be, we need to decide now: are we going to face our emotions, fight them or flee?

DENIAL, DISTORTION & DISENGAGEMENT

I could give myriad reasons (in addition to the couple above) why being emotionally aware and emotionally expressive in a healthy way is non-negotiable in life and leadership but just take a moment to consider why Dan Allender and Tremper Longman, in The Cry of the Soul, find this paramount:

“Ignoring our emotions is turning our back on reality; listening to our emotions ushers us into reality. And reality is where we meet God…. Emotions are the language of the soul. They are the cry that gives the heart a voice…. However, we often turn a deaf ear—through emotional denial, distortion, or disengagement. We strain out anything disturbing in order to gain tenuous control of our inner world. We are frightened and ashamed of what leaks into our consciousness. In neglecting our intense emotions, we are false to ourselves and lose a wonderful opportunity to know God. We forget that change comes through brutal honesty and vulnerability before God.”

THE DOCTOR’S DOCTOR

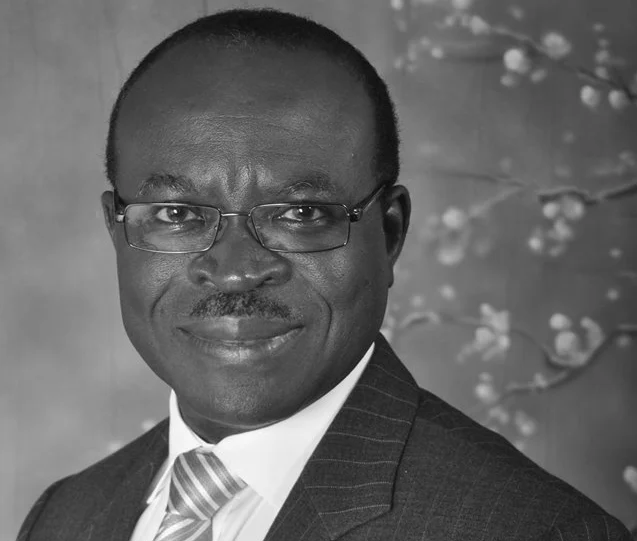

So where do we go from here? Personally, I have not only devoured Scazzero’s The Emotionally Healthy Leader but also led my entire ISMC national leadership team and still taking the fourteen country CEOs of The HuD Group through it chapter by chapter. At ISMC’s recent biennial national staff conference in Montreal, there was a daily ‘Emotionally Healthy’ segment (spirituality, relationship, leadership). In fact, the picture you see above was taken in May 2017, when Anyele and I had the privilege of joining the authors, Peter and Geri Scazzero, at their conference in New York (together with the CEO of The HuD Group Canada and his wife). I’m still learning and eagerly walking with a few others through Emotionally Healthy Spirituality over the next few months.

Having gleaned from Smith that “the genius of good [spiritual] direction is that we probe together, director and directee, and attend to the emotional wake that is left by the myriad of experiences we have had or are having” I have begun a search for a well-fitting spiritual director, apart from the amazing mentors, accountability partners, counselors and coaches I have in my life. And a good practice, encouraged by my wife, has been to “name my feelings,” because “what you name you can tame.”

How about you? Could you too be suffering from emotional constipation? What may God be calling you to do about it? Take a personal Emotional Healthy Spirituality assessment here. Don’t be afraid or ashamed to admit your state of emotional immaturity or bankruptcy, because hey, “God blesses those who are poor and realize their need for him, for the Kingdom of Heaven is theirs.”

Other Works Cited

Barton, Ruth Haley. 2012. Pursuing God’s Will Together. Downers Grove, IL: IVP.

Scazzero, Peter. 2014. Emotionally Healthy Spirituality Day by Day. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Scazzero, Peter. 2015. The Emotionally Healthy Leader. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Willard, Dallas, 2002. Renovation of the Heart: Putting on the Character of Christ. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

4 Comments

Good words, Brother! Campus Ambassadors (of Missions Door) also used The Emotionally Healthy Leader as a basis for discussions last month at its biennial staff forum. I have just a few thoughts that came to mind while reading this blog.

Many leaders of the older generation were taught something quite different regarding emotions, not just in the churches but in the seminaries. It could be called cultural, but at its core it was also theological because it involved one’s view of God. Even at the time I was a “young-un” I found fault with this view, but at that time I was more into pondering than being able to make reasonable arguments

.

Their line of reasoning had its foundation in the immovability of God, supposedly scriptural but highly influenced by Greek philosophy (although that was not readily recognized in conservative, evangelical circles). One element of this doctrine concluded that since God cannot and does not change, he cannot show emotion. Emotions reflect changeability, with our hearts being moved by the circumstances and events around us. Even through Scripture talks about God’s rejoicing over his people and being angry at their rebellion, such imagery was considered anthropomorphic language, with descriptions of God’s character being put into idioms that we mere humans can understand.

The natural result of such reasoning meant that believers, who are given the goal of becoming godly (God-like), must also deny outward display of emotions. Being emotional was considered a weakness, something more inclined to be tolerable in females, who were the weaker sex anyway. [Sarcasm intended.] This one theological teaching ended up controlling not only a lot of human reaction within the church but also creating a lot of guilt. If a leader showed some emotion, he felt obligated to apologize.

The whole issue of anthropomorphic language needs to be reexamined. We are created in God’s image, not the other way around. We have emotions because God has emotions. The difference comes in the way those emotions are expressed. His are pure, the result of a heart that can be moved by the choices of his creation. Our emotions are subject to the corruption of the world. Self-control, a fruit of the Spirit, includes letting the Spirit have command of our emotions—not denying that we have them or that we shouldn’t express them.

We become like the God we worship. If our God has no emotions, then his followers will deny the acceptability of having emotion. If our God does exhibit holy emotion, then emotional maturity in ourselves means feeling and expressing emotions in godliness. We become like our godly Master, the god-man who expressed joy and sadness, thankfulness and anger, all without sin.

Good words, Brother! Campus Ambassadors (of Missions Door) also used The Emotionally Healthy Leader as a basis for discussions last month at its biennial staff forum.

I have just a few thoughts that came to mind while reading this blog.

Many leaders of the older generation were taught something quite different regarding emotions, not just in the churches but in the seminaries. It could be called cultural, but at its core it was also theological because it involved one’s view of God. Even at the time I was a “young-un” I found fault with this view, but at that time I was more into pondering than being able to make reasonable arguments.

The line of reasoning had its foundation in the immovability of God, supposedly scriptural but highly influenced by Greek philosophy (although that was not readily recognized in conservative, evangelical circles). One element of this doctrine concluded that since God cannot and does not change, he cannot show emotion. Emotions reflect changeability, with our hearts being moved by the circumstances and events around us. Even through Scripture talks about God’s rejoicing over his people and being angry at their rebellion, such imagery was considered anthropomorphic language, with descriptions of God’s character being put into idioms that we mere humans can understand.

The natural result of such reasoning meant that believers, who are given the goal of becoming godly (God-like), must also deny outward display of emotions. Being emotional was considered a weakness, something more inclined to be tolerable in females, who were the weaker sex anyway. [Sarcasm intended.] This one theological teaching ended up controlling not only a lot of human reaction within the church but also creating a lot of guilt. If a leader showed some emotion, he felt obligated to apologize.

The whole issue of anthropomorphic language needs to be reexamined. We are created in God’s image, not the other way around. We have emotions because God has emotions. The difference comes in the way those emotions are expressed. His are pure and controlled, the result of a heart that can be moved by the choices of his creation. Our emotions are subject to the corruption of the world. Self-control, a fruit of the Spirit, includes letting the Spirit have command of our emotions—not denying that we have them or that we shouldn’t express them.

We become like the God we worship. If our God has no emotions, then his followers will deny the acceptability of having emotion. If our God does exhibit holy emotion, then emotional maturity in us means feeling and expressing emotions in a godly manner. We become like our godly Master, the god-man who expressed both joy and sadness, thankfulness and anger, all without sin.

Good words, Brother! Campus Ambassadors (of Missions Door) also used The Emotionally Healthy Leader as a basis for discussions last month at its biennial staff forum. I have just a few thoughts that came to mind while reading this blog.

Many leaders of the older generation were taught something quite different regarding emotions, not just in the churches but in the seminaries. It could be called cultural, but at its core it was also theological because it involved one’s view of God. Even at the time I was a “young-un” I found fault with this view, but at that time I was more into pondering than being able to make reasonable arguments.

Their line of reasoning had its foundation in the immovability of God, supposedly scriptural but highly influenced by Greek philosophy (although that was not readily recognized in conservative, evangelical circles). One element of this doctrine concluded that since God cannot and does not change, he cannot show emotion. Emotions reflect changeability, with our hearts being moved by the circumstances and events around us. Even through Scripture talks about God’s rejoicing over his people and being angry at their rebellion, such imagery was considered anthropomorphic language, with descriptions of God’s character being put into idioms that we mere humans can understand.

The natural result of such reasoning meant that believers, who are given the goal of becoming godly (God-like), must also deny outward display of emotions. Being emotional was considered a weakness, something more inclined to be tolerable in females, who were the weaker sex anyway. [Sarcasm intended.] This one theological teaching ended up controlling not only a lot of human reaction within the church but also creating a lot of guilt. If a leader showed some emotion, he felt obligated to apologize.

The whole issue of anthropomorphic language needs to be reexamined. We are created in God’s image, not the other way around. We have emotions because God has emotions. The difference comes in the way those emotions are expressed. His are pure, the result of a heart that can be moved by the choices of his creation. Our emotions are subject to the corruption of the world. Self-control, a fruit of the Spirit, includes letting the Spirit have command of our emotions—not denying that we have them or that we shouldn’t express them.

We become like the God we worship. If our God has no emotions, then his followers will deny the acceptability of having emotion. If our God does exhibit holy emotion, then emotional maturity in ourselves means feeling and expressing emotions in godliness. We become like our godly Master, the god-man who expressed joy and sadness, thankfulness and anger, all without sin. [Carmen Bryant]

Good words, Brother! Campus Ambassadors (of Missions Door) also used The Emotionally Healthy Leader as a basis for discussions last month at its biennial staff forum. I have just a few thoughts that came to mind while reading this blog.

Many leaders of the older generation were taught something quite different regarding emotions, not just in the churches but in the seminaries. It could be called cultural, but at its core it was also theological because it involved one’s view of God. Even at the time I was a “young-un” I found fault with this view, but at that time I was more into pondering than being able to make reasonable arguments.

Their line of reasoning had its foundation in the immovability of God, supposedly scriptural but highly influenced by Greek philosophy (although that was not readily recognized in conservative, evangelical circles). One element of this doctrine concluded that since God cannot and does not change, he cannot show emotion. Emotions reflect changeability, with our hearts being moved by the circumstances and events around us. Even through Scripture talks about God’s rejoicing over his people and being angry at their rebellion, such imagery was considered anthropomorphic language, with descriptions of God’s character being put into idioms that we mere humans can understand.

The natural result of such reasoning meant that believers, who are given the goal of becoming godly (God-like), must also deny outward display of emotions. Being emotional was considered a weakness, something more inclined to be tolerable in females, who were the weaker sex anyway. [Sarcasm intended.] This one theological teaching ended up controlling not only a lot of human reaction within the church but also creating a lot of guilt. If a leader showed some emotion, he felt obligated to apologize.

The whole issue of anthropomorphic language needs to be reexamined. We are created in God’s image, not the other way around. We have emotions because God has emotions. The difference comes in the way those emotions are expressed. His are pure, the result of a heart that can be moved by the choices of his creation. Our emotions are subject to the corruption of the world. Self-control, a fruit of the Spirit, includes letting the Spirit have command of our emotions—not denying that we have them or that we shouldn’t express them.

We become like the God we worship. If our God has no emotions, then his followers will deny the acceptability of having emotion. If our God does exhibit holy emotion, then emotional maturity in ourselves means feeling and expressing emotions in godliness. We become like our godly Master, the god-man who expressed joy and sadness, thankfulness and anger, all without sin.